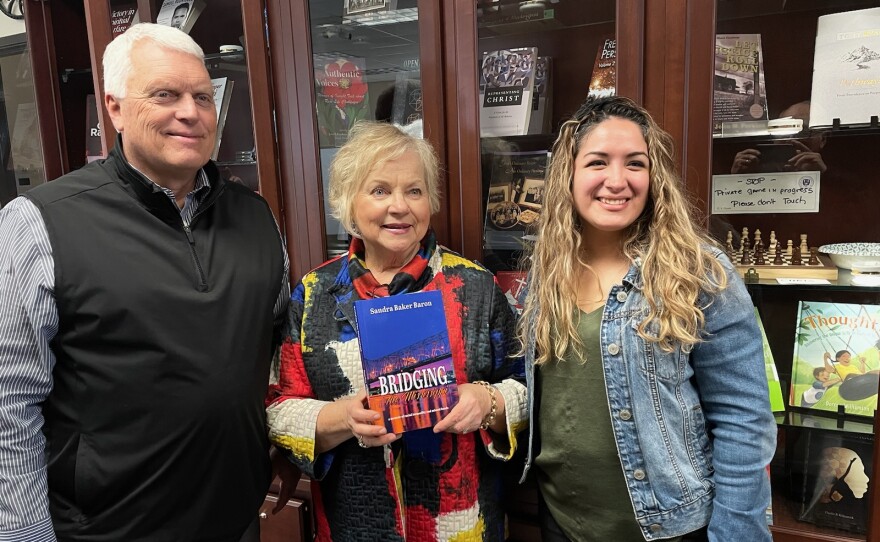

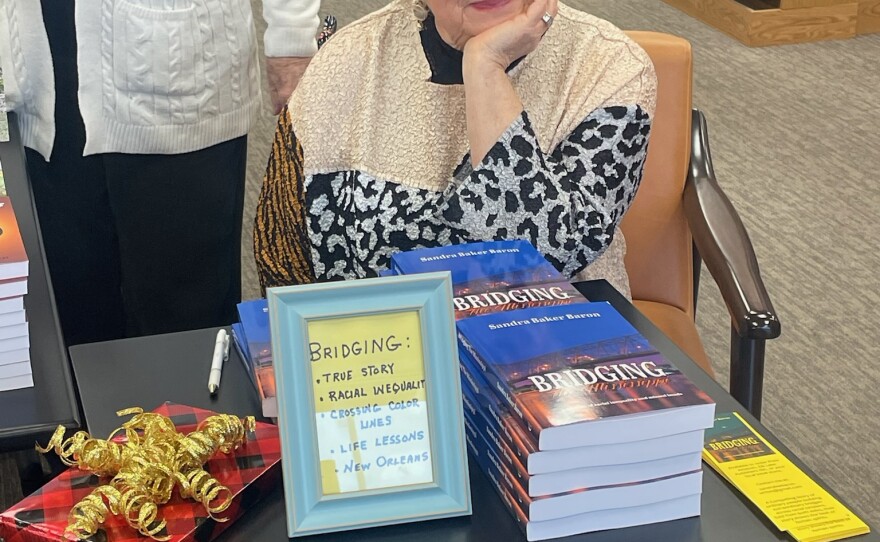

Local author Sandra Baron has written a new book chronicling her and her husband’s first year teaching experiences with the New Orleans school system in 1967 called Bridging the Mississippi: A Memoir of Racial Inequality and Missed Beads.

Not realizing they were the only white teachers at the all-Black, inner-city Carter G. Woodson Junior High until they arrived in New Orleans, Sandra soon discovered that she would teach her students to read and write and they would school her about the realities of their life.

WBOI’s Julia Meek discusses the impact of that school year with Baron and exactly what motivated her to share the story more than 50 years later.

Copies of the book are available from Amazon or Barnes & Noble, or can be ordered from your local bookstore.

You can connect with and learn more about Sandra at the author's website.

Read a transcription of the conversation here:

Julia Meek: Sandra Baron, welcome.

Sandra Baron: Thank you.

Julia Meek: Now you have chronicled your first year of marriage, which is also your first teaching jobs, you and your husband, 1967 was a big year for the Barons, you and Danny were the only white teachers in an all-black school in New Orleans as a matter of fact. What was that like?

Sandra Baron: Well, we weren't aware we were going to be the only white people in an all black school. But when we got there, we just said, Okay, this is where we are and the black community, the faculty reached out to us and the black children reached out to me, and we said, hey, we just have to make do we've got to adjust and learn this culture.

Julia Meek: So diversity and inclusion were actually very different back then. How did you come to terms pretty much overnight just to be able to deal with the challenges that you faced that you didn't even know you're going to be facing till you got there?

Sandra Baron: Well, I just took it day by day, hour by hour. I'd walk in the classroom, I'd have a plan, and sometimes the plan would go right out the window, because the kids you know, I had to get management of the classroom, I had to learn names in order to get their attention quickly. I had to understand Cajun and I had to understand Creole and had to understand black talk of the streets.

And so I had to make a dictionary. And we would start with the dictionary in the morning. I was a language arts teacher, and I was a speech teacher and so it was natural for me to want to make language clear and important and they would write down words for me, then I wouldn't know what those words meant. So they would teach me the words. Sometimes they were very unacceptable and I made that perfectly clear, we did not use that language.

But then most of the time, it was things I absolutely did not know about-- Mardi Gras I didn't know about, the streets of New Orleans, I didn't know about, the customhouse--I didn't know about the slavery. I didn't know things that I should have known, but I was only 22 and I didn't know I was going to an all black area. So they taught me.

Julia Meek: And they enjoyed that. That was their point of pride.

Sandra Baron: Yes, they loved it. In fact, one young man said, "you know, when they bring your check in on Friday, Miss Baron, I'll just take it because I taught you so much this week!" (chuckles)

Julia Meek: Now bridging the Mississippi that term in this case, it symbolizes several things, especially crossing that racial divide. With so few reference points back then, where did you turn when you needed to learn how to cross that racial divide?

Sandra Baron: I turned to the Lord and I have that talk going through the book. But the racial divide to me was just learning another culture. It was not a divide in my mind, it was, I need to know their ways; I need to understand their language, I need to understand what's important to them. And so I just asked, "What did you do this morning? Oh, did you have breakfast?" And they go, "no." Then I'd say, "well, where do you live?" And they'd say, "we don't live--we stay, sometimes, at such in such a street. And sometimes we stay at my grandmother's, sometimes we stay elsewhere."

So I immediately learned that they had a life much more unstable than I had ever known in my own life. And I needed to come to grips with that, that not to have expectations that they were going to act like me or think like me or be like me. And I think that was probably the reality of how I crossed that bridge. I quit expecting them to be quiet and good and still, because that was not their culture to be quiet and good; and still, that was my culture.

Julia Meek: Now the format that you used for this book, it's a memoir. And you've presented 55 chapters, which are lessons you regard them as that. Each begins with a timely passage from various black leaders. How and why exactly were those 55 points chosen?

Sandra Baron: Okay, the book, I didn't want to call them chapters, it was a teaching of the class of the lesson. And so when I would lead into the lesson, I'm a lover of poetry, I'm a lover of quotes, I'm a lover of literature. And so I would remember some quote, or some person that was very dear, and I thought their words were wise and timely, because I live a life of quotes, and they move the book forward.

So they introduce the reader to the concept that I'm going to have to learn that day in order to function as a teacher, as a wife, or as just getting through the day at Carter G Woodson.

I chose contemporary black voices to come along with me because they had knowledge that I did not have. And I wanted them to express that in the quote or tell you a story that you would hardly believe that could have happened in 2022, 2000, that you thought, oh, that could happen in '67 but how is that happening now? So I asked for those stories and they gave me the stories and then that would teach that lesson of that day.

Julia Meek: That's context, that's brilliant. Now you are very vocal about what your classes taught you.

Sandra Baron: Yes.

Julia Meek: You're carrying that through this conversation. What's the biggest thrust of all those lessons that you learned would you say?

Sandra Baron: The lesson that has lasted me a lifetime is "make do", because when I had no books, the other teachers came in and said, "Ah, baby, you'll be all right. Just make do, you'll get through till three o'clock today." I had children that couldn't read and they knew how to maybe write four words. And I'd say, "let's just make a sentence. Let's make do with these four words. I can teach you had to make a sentence with these four words.

Or when we be crossing the Mississippi River and Dennis and I might not be in complete harmony, (chuckles) I would say, "we just have to make do and pretend we're happy right now, because we're at school and we can't go in grumpy!" If we didn't have enough money, you know, as we went through our marriage for a certain month, we just say, "just make do." If somebody needed a home or a short stay with us, we just say, "we have to make do." And to this day, we live by that mantra, we make do.

Julia Meek: Okay, you relied heavily on storytelling throughout that school year, something you had already in your life and something that no doubt has stayed with you all these years. This includes sharing Huckleberry Finn with your classes, you reading it, them loving it. Where could you take all of this the whole wide world of storytelling that you shared with them,

Sandra Baron: I was raised on storytelling, I'm from the south and I had southern roots. And so my uncles told fascinating stories when I was a child, and my grandfather told me stories. So I became a storyteller. That was natural. I even did storytelling professionally for a while. And I thought when I was a teacher, I could get their attention if I could find an interesting story.

A story can get a child to understand something when they're grieving that they cannot understand if you would just try to say, "now a grief is a cycle, blah, blah, blah, blah." So I've always had a number of stories that I could pull out, even to this day, storytelling is very part of my getting to a person where they are and understanding that person and walking in their, in their moccasins, so to speak. So I still tell stories, and I still believe that they get to the heart.

Julia Meek: Does that, by your own definition then, describe the act of putting on a play, which is something else you actually did for these school children the year that you were there? I understand it was probably the first play that they ever did in a big way like that, was that the same kind of purpose and power?

Sandra Baron: Right, that was the main impetus within, if I could teach them to be a part of the story, it would be something bigger than they already were. And they could become someone on stage that maybe they weren't an everyday life, but later on, they could become that person.

So it was very important to me to use drama and the arts and any kind of creation I could use to get to these children and make them interested in learning and make them know that they could be all they wanted to be, that they could become whoever they wanted to be. They weren't locked, you know, on the Mississippi River all their life.

Julia Meek: Could they believe that at that point in time?

Sandra Baron: No, that was a big jump. You read the book, and you read about the play, you'll see I put people in positions, bullies into cooperative positions. And, the teacher said, that's never gonna happen. But it did. It did happen.

Julia Meek: It was pretty brilliant how it did turn out, that's really something. Let's talk about the other gaps you were bridging with these kids, Sandra, including the interaction you had outside the classroom and the school yard.

Sandra Baron: It was important to me, I don't know why, but I just wanted to take the children home with me. So I had some twins and I loved them dearly, and I went to their project and walked through the project and asked her mama, could I take them home for the weekend. And she said, "you can take them home as long as you want. (chuckles)

And so in this day and age, that could never happen, but in the 60s, she knew that I had a heart for her children. We took them home and we took them to the airport, we took them to the movie, and I took them shopping and we got kicked out and we got very harsh words. And I saw racism at the ugliest stage I had ever been in my life.

Julia Meek: Because this was a mixed situation that you were creating, having the girls with you?

Sandra Baron: Right, I took the girls shopping in a very nice place. And they were told to get out and called names and wouldn't take my money. And I had no clue this was going to happen. And so the girls and I then had a bonding, a very special bonding and that's why that I could locate them 50 years later. And they remembered me because I was the white lady that didn't know that blacks couldn't go shopping in a white Mall.

Julia Meek: There were a lot of things that you chose to carry forward because it was the righteous thing to do. And it must have made an impression all those years. And then that definitive tragedy, the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

That happened in the spring, in April of the year that you were teaching down in New Orleans. How did this influence your lives immediately as you lived through and after that tragedy? Where, how could any of you--all of you find positivity?

Sandra Baron: The day after, it was so sad and so quiet and I had never at 22 experienced such a serious, serious thing. My children were sad, the staff stood in circles and said very little. And so I told the children the best I could do for them was just to write their hearts down on paper. Let's write a reaction of how we're feeling and what will we do without Martin Luther King and how will the future go on.

And so they wrote these essays and I carried them around with for 55 years before I returned them to them, but I felt a great need to take those essays back. In the book I give some of the writings of the essays and their feelings and their understanding. I was brokenhearted because I am a dreamer. And I knew that his whole hopes and his dreams were right and that every child deserve the right of equality, no matter whether it was shopping, going for that master's degree, or moving to a state that they want to live in, and his death seemed to thwart all that going to be happening.

But what I did find out is that he had affected some other leaders and leaders in the school where I was teaching. They took that ball and they began to run with it, they took a negative and turned it into a positive, becoming a stronger leader, and they were peaceful leaders, but they were bold. And this act had put new boldness in them and more passion in them.

And the children, I felt, were the same. And they encouraged me. They said, "Oh, it's going to be all right, we're going to find another leader. He taught people just like you taught us, he touched lives, just like you touched us. And those people are going to come alive and be leaders." And they have been--they have come forth. That was a wonderful lesson that didn't make the book, but it made my heart.

And my heart just burst for all these years to tell that story of how we went in there so naive and so unknowing, and we came out with sadness, because of Martin Luther King's death, but we came out with the maturity that it was our purpose on this earth to go across that grid of racism to which crosses colored lines to be a part of a community that maybe we wouldn't be comfortable with; to reach out and have a conversation that would be hard to have a cup of coffee with a black person instead of a white person that day.

And so it was very lasting, and I still read Martin Luther King.

Julia Meek: And you pretty much always knew that you needed to write this book since those days?

Sandra Baron: Right. It was in my heart, it was in my brain. I couldn't dismiss it. I dream about it. I would think I'm having two hard a time getting it published. Maybe I'm not supposed to get this book published. And I'd think, "Well, that's nonsense. This story gives honor to the black community. This story gives honor to the teachers and the hard work that it is to be teaching. And this story gives honor to Martin Luther King, I have to write the story, I have to.

Julia Meek: Good for you that you have, for sure. Now, one point, the subtitle of this book, Memoir of Racial Inequality and Missed Beads, that's certainly a New Orleans phrase. Tell us what that means?

Sandra Baron: The black children, they were only allowed to go one place and stand and watch the parades at Mardi Gras. And the white children were allowed bleachers at that place. So they were higher, and they would throw beads out from the floats into the air--if you've ever been to Mardi Gras, and you reach out and catch these colored beads. But the black children were never allowed to catch them in the air, they were only allowed to catch them if they were missed and fell to the ground.

And in my heart. I knew that the black community had so many missed beads in their lives, that I had to be a part of making that happen for them, that they weren't going to have to wait for a missed bead. They could be where they needed to be--on a bleacher, down below or on the float.

Julia Meek: Good for you and what a wonderful metaphor. And with all that in mind and certainly had an effective title even then, as you're going into writing the book, what did it take, nitty gritty, to get all of this put back together, these reconnections made and you getting this book written?

Sandra Baron: Katrina. Katrina came and I looked at the adults and the children that were on the roofs and they were drowning, and they were starving, and there was no one coming to assist them. And then the waters were raising. And I knew those were my former students and my husband and I both wept and wept when we saw that happening. And that was probably the motivation for me to go and find those students.

And it was very hard after Katrina, two and a half years of research to find the first student. But that momentum moved on. Ironically, Denny being a phys ed teacher, and then an administrator, he had made a very linear outline of our activities of that year. And I did not know he had that outline. But one day, he said, Look, here's my steno book, I have an outline of everything we did all year long. And I go, "you're kidding!"

But I also made an outline, but I made a writer's impact kind of journal outline. So when something hit my heart, or broke my heart that was written so I could assemble those two things together, plus interview the students that were the main characters and interview the teachers that actually experienced it and said, "Is this true? Am I remembering this wrong? Help me! And they said, "No, you are not remembering it as severe as it was. We thought you would be in danger, but you never knew danger. You had no fear of anything. So we actually hid behind windows and walls to protect you, to make sure nothing was going to happen to you."

That was such a blessing to my heart. These people loved us enough to be discreet, but watch after us.

Julia Meek: Utterly remarkable as is your whole journey. And in the end you found five of your students?

Sandra Baron: Found five of my students. The book was written in 2012 and five students I found were the main characters in the book, the book had already been written.

Sandra Baron: That's amazing, only God could do that. Because at first I was discouraged that I couldn't find, but I found Deborah Brown Morton and she's a famous evangelist in New Orleans. And that leads me to I going to do a southern tour in March.

She said to me, it might be okay for you to to sell hundreds of books but that's not okay with me. Your story and your message is so strong and gives honor where no one else has given honor that I want you to sell 1000s. So she's having a very big event in New Orleans on March 11 and then a very big event in Atlanta on March 4.

She has a church of 5000, she and her husband, in Atlanta, and a church of 5000 in New Orleans. And I get to tell the story, and she's going to do some work with me on stage of you know, I am black and this is what I thought; she was white and this is what she thought. So I'm excited.

Julia Meek: That is something.

Sandra Baron: And you know, this was a painful and powerful time for you and your husband. Now some 50 years later, your story is told, how have you two change by now strictly because of that experience would you say?

Sandra Baron: I think mainly, we've talked about that a lot, we will choose to go with our black friends. My own friends, my own teaching always said, "you always gravitate toward black people on the street and we cross over the other side, we've noticed that and you always ask black people for information, you always ask them for directions, you don't even think to ask a white person." And I said, "that's just built in me, I have great trust for the black community and they've taught me a lot."

And it didn't leave me. So Denny and I have many black friends. And they know the story was in my heart and wanted to be written and they really encouraged me. And they said don't let it go. Don't let it go. You know, you may be getting turned down at publishers. They say people don't want sweet stories like this. They don't want, you know, all these things that turn out a bad child turns into a good child.

Well, you know, our worlds upside down now. And people do want a story of hope. And I think that's why the timing is right. The timing is right. It's a story of hope and how we can go forth together hand in hand one and equal and not be disturbed because of the color of our skin.

Julia Meek: And Sandra, what exactly do you hope everyone will take away with them from the story you're so lovingly tell?

Sandra Baron: That they can make do and make anything happen that they want to. I think they'll take away that skin color is not the purpose of our life, but relating with anyone, Hispanic, Black, Asian, that these are people on the earth that have great wisdom, and they have history that we don't have as Americans because we're not that old, and they have so much to share.

So I hope they take away, "You know what, I think I'm going to ask somebody different to coffee this morning."

Julia Meek: Sandra Baker Baron is author of bridging the Mississippi: A Memoir of Racial Inequality and Missed Beads. Thanks so much for doing and sharing this monumental act, Sandra. Please carry the gift.

Sandra Baron: Thank you.

Julia Meek: And where can folks find your book?

Sandra Baron: You can buy it at Amazon or Barnes and Nobles or your local bookstore, they can order it for you. And if someone has questions or further interest or wants me to help them with their book club or wants me to be an inspirational speaker, you can contact me at sandraleebaronwrites.com