What makes a good teacher? Indiana schools have over 200 different answers.

Indiana school districts, in fact, use 242 separate methods to evaluate their teachers, according to a StateImpact Indiana analysis of state data. It’s a messy process that’s led to concerns about erratic practices, inconsistent implementations and incomparable results.

“Teacher evaluation is the very core of improving student outcomes,” says Sandi Cole, co-director of Indiana Teacher Appraisal and Support System (INTASS), a research group studying Indiana’s teacher evaluation systems. “When it’s done well, that’s how teachers improve, how instruction improves and, ultimately, how students improve.”

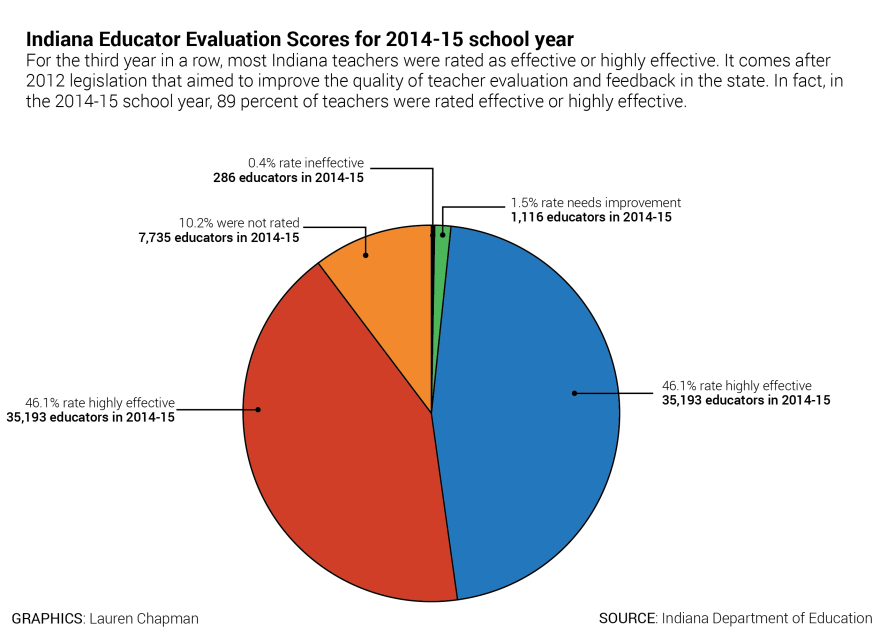

Data show that almost all Indiana teachers consistently score highly on evaluations year after year after year. But INTASS directors have concerns.

Many districts can demonstrate effective structures. But, on a statewide basis, districts have wide-ranging interpretations of law, varied evaluation models and a monitoring system that experts say gives districts little incentive to improve evaluation.

MIXED READINGS OF INDIANA’S TEACHER EVALUATION LAW

Teacher evaluations, in general, stem from a simple concept: review and rate teachers’ performance and effectiveness in the classroom. Then, give them feedback and professional development to improve.

But, in recent years, it’s become complicated — with new statewide requirements.

The Indiana General Assembly passed a 2011 bill that requires schools measure teacher effectiveness based on a combination of classroom observations and student learning, like test scores. Then schools give teachers one of four ratings: highly effective, effective, needs improvement or ineffective.

But, the statewide rules don’t cover everything. The state provides an optional evaluation system, called RISE. District leaders may use it, but they don’t have to. Many don’t.

In Indiana, 45 districts use the state’s RISE teacher evaluation system, 153 districts use modified versions of RISE, 70 districts use locally created evaluations, 25 districts use “other” methods, eight districts use a nationally-developed rubric and one district uses an evaluation system developed at Harvard University.

In total, at least 242 separate measures.

For three years in a row, across evaluation systems, districts rate almost all Indiana teachers as effective or highly effective — but the same ratings may not mean the same thing.

“I don’t think we can say, with certainty, that a ‘highly effective’ teacher is the same across districts,” Cole says.

While the 2011 law requires all evaluation plans contain some of the same measurements, these measurements are not clearly defined.

For example, the law says measures of student learning, such as test scores, must “significantly inform” teacher ratings. That’s left up to district interpretation.

“There is ambiguity in the law in terms of what ‘significance’ means,” Cole says.

Some districts count test scores for as much as 50 percent of a teacher’s rating. Others use student learning goals for 60 percent of rating. Others use those factors for as little as 2 percent.

“There is a lack of consistency among how plans are being developed and how plans are being implemented and how plans are being monitored,” Cole says.

Much of it, comes down to two factors: local control and pay.

LOCAL CONTROL VS. STATE MONITORING

Teacher evaluations can be a case-study for tension between local control and statewide standardization. State law lets districts decide what type of evaluations they use and how those are constructed. But the Indiana Department of Education is in charge of monitoring teacher evaluation systems.

To evaluate the 2011 law, the Indiana State Board of Education and the Joyce Foundation provided funding for INTASS. The group designs, implements, and monitors the quality of teacher evaluation systems in districts throughout the state.

INTASS co-director Hardy Murphy says local control, like having teachers a part of creating their evaluation system, is essential. Still, he says, all districts need to be held to a similar standard.

“The very nature of inconsistency says there are a lot of local decisions being made, that, in some cases, don’t meet state standards in terms of compliance for plan development and implementation,” Murphy says.

Districts’ plans differ widely in how they use measures, such as test scores and school letter grades, in teacher evaluations.

Indiana State Teacher Association president and kindergarten teacher Teresa Meredith says ineffective teachers shouldn’t be in the classroom, and it should be up to local districts to determine who those teachers are.

“When you’re looking at a high needs school with high poverty, students who are very transient or a high population of English Language Learners, there are different things you might be looking for,” Meredith says. “It’s hard to say that one blanket evaluation really fits everybody, but I like the notion of some kind of a framework that school systems can build around.”

Yet, in Indiana, INTASS found that nearly one in five districts do not use measures of student growth on standardized test scores in teacher evaluations, a requirement under state law.

“The legislature specified multiple requirements for evaluation plans but left it to local districts to determine how they meet those plan requirements in ways unique to their school communities,” said Samantha Hart, Indiana Department of Education spokesperson, in an email.

But INTASS’ Cole says that under state monitoring, there’s little consequence for districts with ineffective evaluation — and little incentive for districts to improve evaluations, if they’ve met the law’s loose standards.

“There’s no consequence at this time,” Cole says. “And there’s really no incentive.”

TEACHER PAY AND EVALUATIONS: A STICKY RELATIONSHIP

To complicate matters, Indiana’s 2011 law requires districts to directly link teacher ratings to their pay.

“We thought we had a certain group of teachers that were not being effective teachers,” says Sen. Dennis Kruse, R-District 14. “We wanted a more rigorous system than we had.”

Kruse wrote the 2011 teacher evaluation legislation. His goal? Find and weed out bad teachers. The law bars teachers rated ineffective or in need of improvement from receiving any raise the following year.

“If you’re an ineffective teacher I don’t think you should be qualified to get a raise just because you’re there year-after-year,” Kruse says.

Kruse credits that part of the law for resulting in almost all Indiana teachers consistently receiving high marks.

“A lot of those ineffective and needing improvement teachers have actually been dismissed or they have quit once they don’t get raises for awhile,” Kruse says. “That’s deleted a lot of the low-performing teachers.”

After pushback, in 2016 legislation, first and second year teachers are now eligible for raises, regardless of rating.

But INTASS researchers Cole and Murphy say the original law can discourage evaluators from accurately saying when a staff members needs additional support, if they think someone deserves a raise

“If, in fact, we believe that teacher evaluation is intended to support growth of teachers no matter their rating, then it seems that the compensation model and compensation law is in direct conflict with that,” Cole says.

They say tying pay to evaluation turns teacher evaluations into a system focused on punishing ineffective teachers rather than supporting teachers to increase student learning.

DOING IT RIGHT: MSD WASHINGTON TOWNSHIP

In an effort to highlight districts that have effective teacher evaluations, the state board of education and INTASS recognize districts with effective evaluation systems.

The Metropolitan School District of Washington Township was recognized for having an evaluation system that is a “supportive, collegial, and transparent.”

Like 70 districts in the state, MSD Washington Township designed its own teacher evaluation method.

“We focus on the planning and preparation for classroom instruction, the actual delivery of the instruction, and the professional responsibilities we expect teachers to show on a daily basis,” says Jon Milleman, assistant superintendent of MSD of Washington Township.

The district bases 80 percent of a teacher’s rating on those observations and 20 percent on student achievement, like growth in student test scores.

Milleman says an important part of their teacher evaluation system is an district monitoring committee made up of classroom teachers. That, he says, gives everyone a clear picture of what’s expected.

“It really is to elevate the teaching and learning in the district,” Milleman says. “That’s should be the purpose of an evaluation system.”

LOOKING AHEAD, A NEW FEDERAL EDUCATION LAW

For years, the George W. Bush-era law education law No Child Left Behind gave states specific requirements about teacher evaluation, but in coming months that all changes.

Under the nation’s new federal education law, the Every Student Succeeds Act, the federal government takes a major step back from this issue. The role they require states to have in the teacher evaluation process essentially evaporates.

ESSA eliminates a requirement that districts base teacher evaluations on students’ standardized test scores. Instead, it lets individual states have full control.

The state says this won’t change its practice.

“While ESSA is not prescriptive about local educator evaluation systems, Indiana state law has not changed,” said Indiana Department of Education spokesperson Hart, in an email.

The State Board of Education will continue to work with INTASS to teacher evaluation systems. INTASS’ Murphy says the state’s teacher evaluation system as a whole has gotten better since 2011, but there’s still much room for improvement.

“Is it more effective now than it was? I think the answer to that is yes,” Murphy says. “Is it as good it could be? I think the answer to that is, just like anything else, it can be made better.”

HOW DOES YOUR SCHOOL RANK EDUCATORS?

Database not loading? Click here to view database.