Next year, Fort Wayne will start construction on a 5-mile tunnel about 200 feet under the city.

Later this year, officials will decide what company will do the work. WBOI’s Lisa Ryan wanted to get below the surface of the story, so she went underground to find out why the city is building the tunnel.

Why is the city building a tunnel?

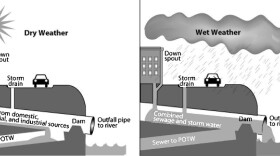

The city’s sewers are kind of like the drain of a sink, and when it rains, the faucet is turned on. As long as nothing is clogging the sink, and there isn’t too much water, it drains easily.

Now imagine filling a bucket of water and dumping it down the sink. Not all of that water can go down at the same time, and the water becomes backlogged and has a difficult time draining.

When the sewers overflow, they carry chemicals from groundwater runoff and household toxins into the rivers--and yes, that includes human waste.

That’s exactly what happens to the city’s sewage system when it rains. Fort Wayne has a combined sewer system that carries both household waste and water from the street. Ideally, the water is taken to the Water Pollution Control Plant to be treated. But sometimes that drain has too much water-- from heavy rains or melting snow-- and it overflows into the city’s rivers. This is called a combined sewer overflow.

This was an acceptable practice when the city’s combined sewer system was designed in the 1860s. It wasn’t until the Environmental Protection Agency was formed in 1972 that the government decided this was bad for the rivers.

Why should residents care?

When the sewers overflow, they carry chemicals from groundwater runoff and household toxins into the rivers--and yes, that includes human waste. People can get sick when they come into contact with water after a sewage overflow has occurred.

David Kohli is the co-chair of the Northeast Area Partnership. He says people have become more aware of the rivers and want to use them for recreation, but can’t if they’re filled with bacteria. And there’s another reason why Kohli thinks people should care about combined sewer overflows. He’s been trying to stop the overflows since 1995, when he found out they were causing sewer backups in basements.

“People were really getting freaked out, because they had to go down there with rubber boots, rubber gloves, they had to use bleach to clean it out,” Kohli said. “I mean, everything in their basement as they had it there, it was destroyed, completely destroyed by this, because you couldn’t utilize anything with all that backup in the basement.”

The city started taking steps to stop basement backups and overflows before the federal government mandated the changes. Now, the EPA is requiring cities to reduce the number of times sewage systems overflow into the rivers.

What will the tunnel look like?

"Tunnel construction is different than, say, vertical construction, building a skyscraper, where you're just going in the air and you can see everything you’re actually working on."

Fort Wayne is planning to build a 5-mile tunnel about 150 to 250 feet deep. That’s about the height of the Allen County Courthouse.

It’s similar to the tunnel Indianapolis has already started to build for the same reasons, but Fort Wayne’s tunnel will be slightly smaller. The boring machine will dig a hole 16 feet in diameter, and then crews will pour a concrete liner a foot thick.

Geologist Leo Gentile is the manager for the Fort Wayne project. He says the hardest part of tunnel mining is not being able to see what’s there.

“Tunnel construction is different than, say, vertical construction, building a skyscraper, where you’re just going in the air and you can see everything you’re actually working on,” Gentile said. “A tunnel is constructed by its very nature underground.”

"If the rock isn't strong enough, there is the potential for the tunnel to collapse on itself."

Gentile would know the challenges of digging underground. He’s been involved in 100 miles of tunnel construction. He says cities can find the best places to dig by taking samples of the ground, which is one of the first steps in the construction process.

That process is now over for Fort Wayne, and geologists have started analyzing the data to see where the best place to dig would be.

“The more information that we can characterize and provide that to the contractor, the better pricing the city of Fort Wayne will obtain,” Gentile said.

Gentile also has the benefit of being able to see what’s under Fort Wayne’s soil in a large-scale, open diagram. In fact, anyone can see it. From the observation deck overlooking the quarry just north of the Fort Wayne airport, anyone can see the layers of earth under the city. Gentile says the less layers in the rock, the better for mining the tunnel.

“Initially the ground is sort of unsupported, he said. “If the rock isn’t strong enough, there is the potential for the tunnel to collapse on itself.”

What can Fort Wayne residents expect?

As construction is happening, the residents who will be most affected are the ones whose houses are in the construction path. It might be harder for these residents to get to their homes. The path stretches from Foster Park in a curved direction through downtown. City Utilities spokesman Frank Suarez says it won’t be much different than any other construction project.

“Mostly people will see construction in some of the neighborhoods when the drop shaft is being constructed and that will be just like any other construction project: very dirty, a lot of big, heavy equipment, and that will be something that people notice,” Suarez said.

Kohli says the city has done a good job communicating with affected neighborhoods and working with residents that need assistance, including those with disabilities who rely on deliveries or community transportation.

“The city is helping them as much as possible with that, they’re trying to get them through this time of construction,” Kohli said.

Suarez says the project will cost about $150 million. The combined sewer overflows will be brought down from an average of 71 times per year to no more than 4 times per year for the St. Marys and Maumee rivers. Which means a healthier environment, more recreation on the rivers and cleaner basements.