Cuts to federal funding, inflation and a drop in available goods are affecting food banks around the country. For people who rely on rural food pantries, many of whom live in designated food deserts, continued rising costs can escalate food insecurity.

Earlier this month, the USDA announced it would be cutting $1 billion for programs that pay local farmers to provide food to local schools and food pantries. Scheduled deliveries through the Emergency Food Assistance Program are also being halted or cut back.

Pastor Roy Nevil runs the food pantry out of Poneto Faith Community Church in Well County. He said, while they receive a lot of the Emergency Food Assistance Program, or TEFAP, food from Community Harvest, he also receives donations from larger grocery stores like Walmart and Kroger.

But inflation and the rising cost of goods, with demand lowering, mean stores order less food, which means they have less leftover to donate.

“When your dollars become worth less, then the manufacturers ‘we can’t afford to be making all of this and sending it out when no one buys it.’ Then, what?" He said. "What do we do now?”

The TEFAP program also isn’t what it used to be.

Nevil said he doesn’t know exactly what the suspension of federal funding will mean, but they’ve been dependent on TEFAP to help run the food pantry. He said Poneto can make it for a while, but he doesn’t yet know for how long or what the contingency plan will be.

“We’re gonna be having to put more money out to go buy stuff, you know, and go pick it up and bring it down. It’s gonna be a little more expensive," Nevil said. "I mean, it won’t put us under, but at the same time it does make a difference.”

Nevil said around April or May of 2020, when the COVID pandemic was moving through the country, the floodgates opened, increasing funding and food for food banks and pantries.

Toward the end of 2021, funding began lessening and in early 2022 dropped drastically. He was still working with Community Harvest in Fort Wayne at the time and said toward the end of 2023, the produce shelves were empty.

Nevil said that the rise in costs has left the funding worse off than it was before the pandemic.

Poneto’s food pantry manager, Denise Heiniger said while they haven’t seen an uptick in unemployment in the area, she does see more and more older kids making use of the pantry.

Heiniger works at the local schools, so students are familiar with her and know she also works at the food pantry. She said they’ll find her at school and ask about coming to the pantry.

“It’s all sad, it breaks your heart," Heiniger said. "They’re not worried about themselves. They’ve got four half-siblings coming home with them today and they don’t know what they’re gonna feed them. Grocery prices are so horrible that families can’t do it.”

In Warren, the Bread of Life Food Pantry puts their focus on feeding the children, with several things they do special for families with children. Here, the pantry is run like an assembly line, with each volunteer knowing their station and how to operate it.

While the pickup runs like a drive through, volunteers inside fill a grocery cart with goods that every car or family will receive; such as toilet paper, spaghetti sauce and frozen cookie dough. For families with kids, they get all of those things, plus things like cereal, fruit snacks and mac n’ cheese.

Rose Broyles manages the Bread of Life pantry. She said kids are central to their mission because she believes adults can find food, but kids can’t.

“Every family, one to three, they get a gallon of milk and then families with four or more, we give them a voucher down here to the Warren Marathon and they can go down there any time of day, just hand them the voucher and they get a gallon of milk," Broyles said. "And they are treated with respect and dignity. It’s beautiful.”

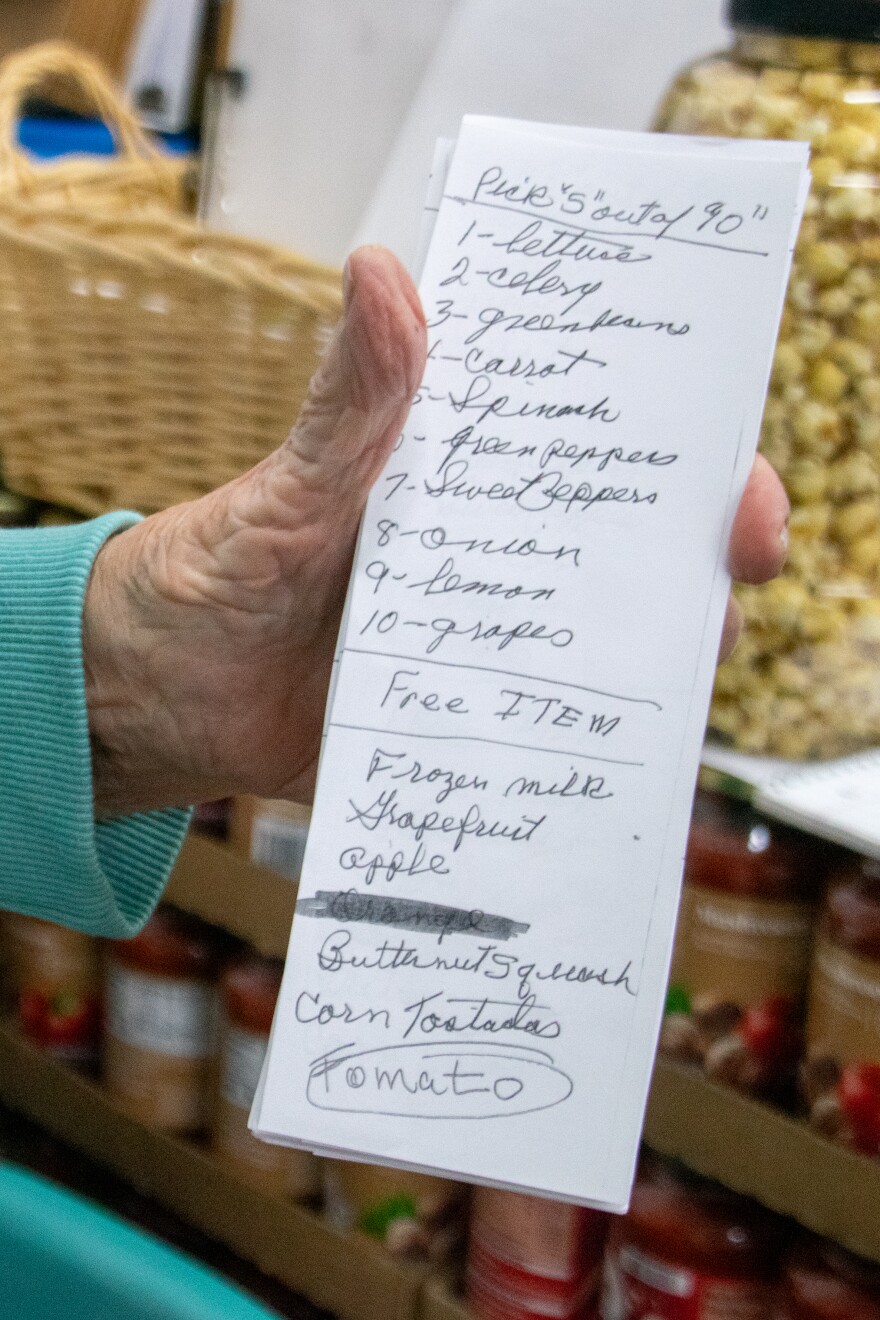

While the carts line up to be filled inside, outside cars file into two lines; families with kids and families without kids. Between the cars, two tables are full of produce for clients to pick from as volunteers load their cars with food. One volunteer hands out slips of paper with a handwritten “menu” on it for clients to choose from.

At the door, a volunteer with a clipboard marks down clients. Occasionally, a volunteer from the cars yells out a number of kids to the volunteer by the door who then relays the message down the hallway to those filling the carts.

The system is efficient and routine, each volunteer knows their spot and most have been working the same station for a long time. Broyles moves around the space, checking on inventory, sharing information and catching up with the volunteers.

There’s a jovial atmosphere inside the pantry. Volunteers share jokes and tease each other, clearly happy just to be part of the assembly line that gets food into family’s cars. The pantry averages about 50 clients.

While the pantry is well-stocked and mindfully run, it’s not immune to the same troubles facing the rest of the food industry. Broyles points out a box of eggs on one of the tables.

“We just lost our egg contract to the bird flu," she said. "Nine hundred and fifty thousand birds are dead now. So, this is our last week of giving out eggs and so we’re giving them just to the families with kids.”

At both Poneto and Bread of Life, there’s a familiarity between the volunteers and the clients. Many families are returning customers. Broyles said she doesn’t worry about people coming through every week, because she knows some families live in nearby hotels and can’t keep things refrigerated or have limited options for cooking.

Heiniger tells her volunteers it's not worth it to worry about people who may be trying to take advantage of the system.

"You know you have people take advantage, you know that coming in, but it is that one family that is down to nothing, that are so appreciative," she said. "That makes it all worthwhile.”

With rising costs and unemployment, plus a lack of supply, more people are in need of food pantries that may never have used one before. The trouble can be getting people to set aside any pride or shame they may feel about it and utilizing the resource.

Nevil said he believes the most effective way to get people to come to a food pantry is to not make it feel like they have to and to approach them without judgement. Heiniger said her approach is to phrase it as them helping her out.

“‘I have an abundance of stuff I need to get rid of, you would really be doing me a favor if you would come and get some.’ So that’s what I do," she said. "And I’ve served more people that way than I have any other way.”

Further north, up in Ligonier, the West Noble Food Pantry has its own unique set of problems. While Poneto and Bread of Life are affiliated with local churches, West Noble is an independent entity.

Lisa Pfenning is the director of West Noble. She said they’ve tried to create partnerships with local businesses and churches, but nothing has really taken hold. Pfenning said in the past four years, clients at the pantry have more than doubled, while TEFAP goods have been cut.

“How am I supposed to do this when I’m not getting bread? And, I’m not getting as much produce, I’m not getting as many baked goods," she said. "How am I supposed to feed the extra people?”

Pfenning said West Noble has an overhead that most other food pantries don’t. She has to pay rent and bills for the space they operate out of. She also doesn’t have a large pool of volunteers.

While Bread of Life and Poneto are able to brush it off when people abuse the system to get extra food or more than they need, it’s harder for Pfenning. West Noble operates every week, but clients are asked to wait a month between visits due to the low supply. Several clients come back early anyway, but she doesn’t turn them away.

“We need help getting things in, we need help volunteering, we need help financially, we need food, we need… a lot," Pfenning said. "And we’re crammed in this little hole down here. It’s hard, it’s rough, but there’s a lot of hurting people.”

While an instinct might be to hold a canned food drive or buy and donate groceries to local food pantries, Nevil said that actually isn’t the most effective way to get food into people’s hands.

“I totally understand. We’re just the conduit taking your donation, putting it out," he said. "I’m just saying if you gave us money, we can take it and buy the stuff at our rate and multiply that over, several times.”

The pantries get special rates from grocery stores, so Nevil said he’s able to take a $20 donation and turn it into 100 pounds of meat or 20 cans of vegetables.

Conversely, Pfenning said the West Noble pantry goes through 400-500 boxes of cereal and 1200 rolls of toilet paper in a month.

“It would be easier if groups pulled together and just bought soup and brought me 500 cans," she said. "That would get me through a month or two.”

Volunteers at the food pantries keep their good spirits, despite the cutting of funds and dwindling supplies. Volunteers at Bread of Life pass around ice cream cones halfway through their shift. Heiniger and Nevil laugh over stories of past clients.

Heiniger said if she could do this work full time, she would.

"It’s fun," she said. "When I stop having fun, I’ll quit.”

For more information about food pantries and hours of operation throughout Northeast Indiana, Indiana 211 offers a search by location function.